By John W. Barry –

Mention the late Levon Helm to a fan of Americana music and you’re likely to get a very strong response.

The quick comeback could focus on The Band, for which Levon played drums and mandolin, and sang. And there are, of course, those iconic Band songs that Levon sang, “Up On Cripple Creek,” “Ophelia” and “The Weight” among them.

Levon and The Band performed and recorded with Bob Dylan. Levon played on Ringo Starr’s First All Starr Band tour in 1989. And after recovering from cancer of the vocal cords and nearly losing his home-recording studio to the bank, Levon during the early 2000s staged a colossal comeback.

And after recovering from cancer of the vocal cords and nearly losing his home-recording studio to the bank, Levon during the early 2000s staged a colossal comeback.

His winning formula revolved around house concerts he held at Levon Helm Studios in Woodstock, New York, that he called the “Midnight Ramble.” What started out as rent parties and a last hurrah ended up saving Levon’s home and setting him on a path to triumph. The Midnight Rambles were presented to a bankruptcy judge as a source of revenue, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Rambles drew sold-out crowds and attracted the likes of Emmylou Harris and Ricky Skaggs. These intimate performances set the stage for three Grammy-winning solo albums, and as they reconnected Levon to his loyal fans, the Rambles introduced him to new ones.

But for all that he accomplished in the music industry, the Levon Helm that I got to know, while collaborating on a book with him, has more to do with things that may seem a bit more, well, routine.

When I think of Levon Helm, I recall the guy who grew up in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, and never lost his passion for farming, tractors and harvest time. Let’s not forget that the Midnight Rambles were based on the traveling medicine shows Levon saw as a kid, growing up in Phillips County, Arkansas. And his 2007 comeback album was called Dirt Farmer.

The Levon Helm I knew loved to watch college football. He indulged his passion for sushi and Popeye’s chicken. And he liked a lot of ice in his beverages of choice—Coca Cola and Boylan’s grape soda—which he drank in a red plastic Solo cup, slipped inside another red Solo plastic cup.

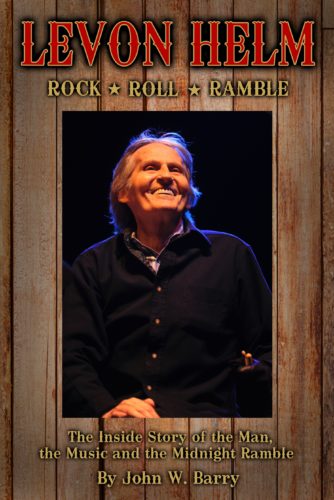

In the wake of Levon’s death in 2012, I continued to work on the book we were collaborating on. Levon Helm: Rock, Roll & Ramble—The Inside Story of the Man, the Music and the Midnight Ramble was recently published and I think that Levon would have been as proud of the final product as I am.

One reason for this is that Rock, Roll & Ramble—with a foreword written by Ringo Starr—covers the ups and the downs of Levon’s life, rather than just his successes.

I traveled often with Levon during his Midnight Ramble era, and during those trips to concerts in the Northeast, and a journey on his tour bus to Bonnaroo in 2008, I recorded our conversations and used them to write the book.

In February 2009, I was traveling with Levon from Manhattan back to Woodstock, after the Levon Helm Band had performed on “Late Night with Conan O’Brien.”

This was during the early stages of the book and I asked Levon if he was comfortable talking about his cancer, his bankruptcy and nearly losing Levon Helm Studios to foreclosure. I am paraphrasing here, but he replied by explaining that a stool needs three legs to work properly, and if you only have two legs, it’s going to fall over. In other words, Levon was saying, we needed all three legs of the stool—we needed to tell the entire story, his entire story.

And so I am very proud to present these excerpts from that story, from Levon Helm: Rock, Roll & Ramble—The Inside Story of the Man, the Music and the Midnight Ramble:

“We were just about at the end of our rope financially,” Levon said. “So the Midnight Ramble was going to be one big rent party or go out with a bang. We were going to have one more tear ‘em down night or two, and all of a sudden, the thing started getting legs of its own and people started wanting to come and pay to get in.

“That was just about the time when the shit was ready to hit the fan. All of a sudden, you’re sick and you can’t work and you haven’t been able to work and the bills don’t stop and they’re still coming in. You’ve got your hands full trying to get well, and then to have the other stuff heaped on top is certainly an unfair way to go. Those radiation treatments, after a while, they can get ahold of you. It’s a little bit raw. The bankruptcy part—that was just getting ready to cloud over and really rain—that don’t scare you after all that radiation.”

On growing up in Arkansas:

“I’ve been to all day sing-alongs with dinner on the ground,” Levon said. “They’d lay out those cotton sheets—a big row of them. And putout a couple of tubs of iced tea at the end of one of them; another tub full of Kool-Aid. And all up and down those cotton sheets would be platters of cold fried chicken and coleslaw and potato salad. My mom would always make chicken salad. I would stand right in front of her chicken salad while the blessing was getting said and I’d attack that first.

“I’d go up and down the row of sheets, looking for stuff like angel food cake, things I’d never seen before. That angel food cake was something else. That was the wildest damn thing I’d ever chewed on. Anything you could chew on that was cold, they’d have a bunch of it. It was all gospel groups. In the morning part would be the local church and their choir people. Then everybody’d eat dinner, then other churches would bringin their choir. I could eat, fight and raise hell and listen to music all at the same time”

On The Band, Band manager Albert Grossman and Bob Dylan:

“There weren’t any real albums after the first two, first three. Everything else was ‘Best of,’ ‘Live at You-Know-Where.’ The Band was just a miserable fucking deal. The Band wasn’t never no fun, shit. The Band always, you know, Albert always wanted to lock everyone in the room, have that stand-offish bullshit, like with Bob. ‘You can’t see Bob.’ Fuck all that, you know? I don’t want to be like that. Shit. There is a lot of arrogance to that bullshit. In fact, that’s why I never could stomach that shit. That ain’t me. No. Uh-uh.”

On the Midnight Ramble:

“The easiest thing I’ve ever done. The whole place turns into a temple for me. There is nothing else and time and everything else is kind of suspended. All I’m conscious of is the pitch, if the pitch is correct. There are no echoes or fancy sound devices. And about 50 percent of what you hear, even on a full electrical tune, is acoustic.

“And walking out of your living room and playing a show—it’s the best. It’s the best. Especially the way the room responds. All I have to do is go shave, take a shower and head out there. We usually stop when it feels like it’s time to stop. When the show’s over, I just walk next door and take my boots off. I believe this might be my payback for all the traveling and stuff. Musicians, their years are like dog years. All that traveling around and now, all of a sudden—I don’t know how we got it to happen. They’re coming here and we don’t even have to crank a car. We leave everything set. And we’ve got all my best equipment; we can sound better here than we can anywhere.

“Each band plays at least an hour, and we probably play at least twohours. By the time we quit, which is between 11:30 and midnight, they’ve had four-to-five hours of music and that’s just about enough in one day. You really can lose the outside world and all those aggravations. At the end of each tune, you can kind of feel that embracement, where you start to realize—music being medicine, you know?

“There is no pressure around here. When you play, you can start prettymuch and finish when you want to and play what you want to. We try to leave it that way, let it be what it wants to be.”

And here are some of my thoughts from the book, as the author, regarding Levon Helm:

When Levon sang, you could feel your own heart aching in his voice. The conviction with which he sang gave you courage. His signature vocal tone was part growl, part roar, part plea for help and it served as a lightning rod for all of our troubles, not just for a few hours at a gig, but across generations.

When Levon sang—with one turn of a phrase, one note, one lyric—he somehow managed to capture the despair we all feel, the hope that keeps us going and the resolution for which we never stop longing. He tapped into that terrifying sensation of solitude that every one of us has experienced, at those times in our lives when you feel like you haven’t got a friend in the world. But Levon also made you feel like he was right there with you, clinging desperately to any solid ground that remained, as his world fell apart in a manner that wasn’t much different than the way in which your world might be falling apart.

Levon Helm had resolve. He did not give up. And he maintained that

sparkle in his eye and that laugh in his gut through all the calamity. Levon Helm represented much of what we value in those we admire, and a lot of what we wished to be true of ourselves.

All of this resonated so strongly with his audience because just like you and me, Levon was forced to manage the madness of life and make sense of insanity. There was a bond of familiarity he shared with millions of people he never met.

To quote Levon about Levon, “There was a guy who never met a stranger.” Here’s a Coke, have yourself a chair, I’m glad to know ya.

John W. Barry first met Levon Helm while working as music writer for the USA Today Network/Poughkeepsie Journal in New York’s Hudson Valley.

You can learn more about Levon Helm: Rock, Roll & Ramble by visiting rockrollramble.com and https://amzn.to/3Q7FHOI.