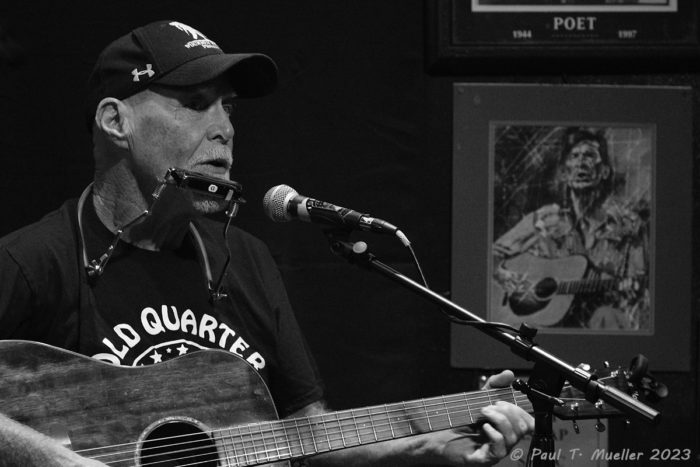

By Paul T. Mueller –

It might sound like an unlikely pairing for a singer-songwriter show – a famously curmudgeonly Anglo man in his early 60s and a Korean-American woman in her mid-40s. But the recent five-week tour featuring James McMurtry and BettySoo has been, by all accounts, a big success. The two wrapped up their current tour at Houston’s Heights Theater on October 7, with McMurtry rewarding longtime fans with an excellent full-band show and BettySoo charming those already familiar with her work and likely winning new followers as well.

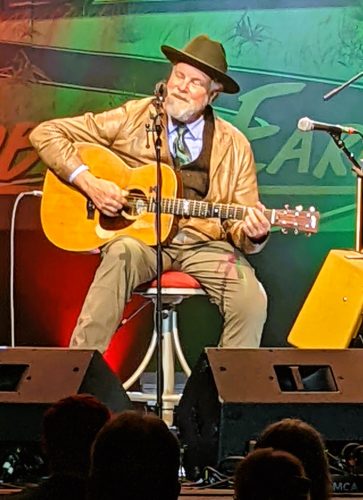

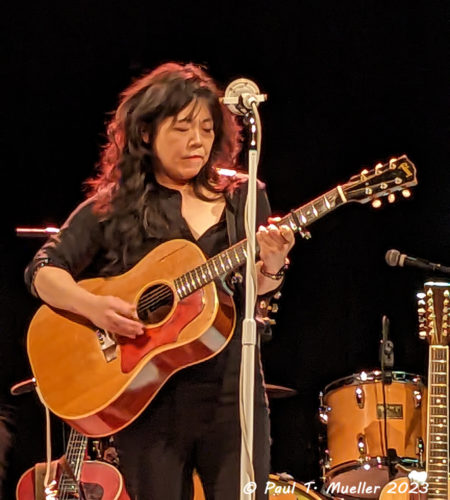

BettySoo opened with a well-received set that included five songs performed solo and four with the backing of McMurtry’s drummer, Daren Hess, and guitarist Cornbread, who plays bass for McMurtry. BettySoo, who owns a lovely voice and impressive guitar skills, put both to good use in service of some well-written but mostly downbeat songs about romantic difficulties, such as “One Thing,” “Down to Nothing,” “Don’t Say It’s Nothing” and an as-yet-unrecorded song that might be titled “Just a Matter of When.” The band-backed selections included the haunting “Blackout” and a nice cover of “What Do You Want From Me Now?,” which she credited to fellow singer-songwriter Ralston Bowles. She also won applause for her defense of oft-maligned Houston, noting that she had grown up in the Houston suburb of Spring.

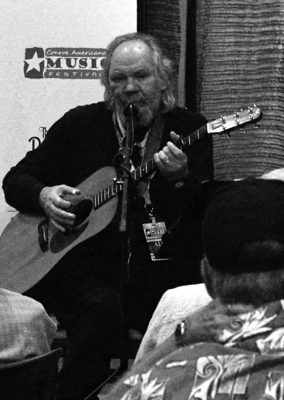

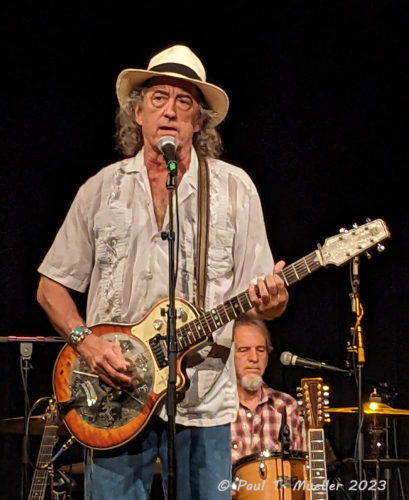

For his part, McMurtry drew from a wide cross-section of his extensive catalog, opening with “Fuller Brush Man” from 1995. Three songs later came “Canola Fields” from the most recent collection, 2021’s The Horses and the Hounds. Other highlights of the 14-song main set included the raucous family-reunion tale “Choctaw Bingo,” wryly introduced as “a medley of our hit”; a solo, unplugged take on “Blackberry Winter,” from Horses; nice renditions of “You Got to Me,” “Levelland” and “No More Buffalo,” and a rousing “Too Long In the Wasteland,” the title track of McMurtry’s 1989 debut album, to close. McMurtry accompanied his distinctive vocals with impressive work on a variety of guitars, both acoustic and electric, while outsourcing some of the six-string duties to guitarist and accordionist Tim Holt.

After a short break, McMurtry’s band returned to the stage and launched into a well-done rendition of “That’s How I Feel,” an instrumental by The Crusaders, a jazz band that started out in Houston in the 1960s. It was a nice tip of the hat to some local heroes. When McMurtry and BettySoo returned a few minutes later, both were in drag – BettySoo in a sharp-looking men’s suit, McMurtry in a stylish red dress accented by a black beret and scarf, two strands of pearls, fishnet hose and red lipstick. The crossdressing originated a few weeks ago in Tennessee, as a dig at politicians seemingly obsessed with the dangers of drag shows there, and seemed almost inevitable for a performance in a state where many elected officials seem equally unsettled by gender issues. The one-song encore was the longtime favorite “Lost in the Back Yard.”

McMurtry, not known for a talkative nature or outward displays of happiness on stage, stayed true to form, with the exception of the occasional comment on a song. But he did seem comfortable and genuinely appreciative of his audience, and also had good things to say about BettySoo and about his son, Curtis McMurtry, also a singer-songwriter (and, as it happens, the driving force behind BettySoo’s 2022 release Insomnia Waking Dream).